The potential of the indie development

When I was twelve, the teacher started asking the students of my class what we would want to become, professionally, when we grew up. When she asked me, I said something like: Well, I’m not sure… I want to do things for people. To which she answered: Very good, you want to work on philanthropy. But then I replied: Well, not exactly; when I say doing something for people I mean something more like… a bridge!

What I wanted to say but I didn’t know how to put in words was: I want to have a creative job. I want the result of my effort to be something new, something that did not exist before I sit down to it. And I want it to be appreciated by people.

That definition of my perfect job can fit very well with architecture, one of my youth passions. Whilst my knowledge on that area are very limited, architecture is an art that call my attention very strongly. I usually dream with buildings, and I mean buildings that don’t exist, that I design on my dreams and that are so aesthetically, useful and awe-inspiring that I remember them for years. I would have been happy being an architect.

But I ended up studying software engineering. And I could not be happier with that. Software engineering is the most rewarding engineering, since it works only with computers; which, at the same time, are the best machines ever, insofar as they act as an extension of our minds, not of our bodies. That liberate us from the enslavement of the physical realms, allowing our creative impulses to fly wild and free, with no more limitations than the ones imposed by the hardware we work on. Consider that: If I had become an architect, I would have never seen any of the buildings I dream about come to light. However, being a software engineer and a game developer in particular, I can make people have an amazing time while living in them. I do not need a thousand of workers and millions of dollars. I just need a PC. And, if I do my job properly, they will remember this time as vivid as a holiday time. Amazing.

Computers, as a medium, not only allow us to create more with fewer resources. They allow us to reach more people. I didn’t have many occasions while I was a teenager (or even on my twenties) to play –paper and dice- role playing games, but it’s an activity that I love. In particular, I like playing as a game master, writing the plot and bringing it to life for my players. But now, I can do it not only for a few of my friends, but for a virtually endless amount of people, thanks to the advancements on the game technologies and the indie phenomenon. Again, amazing.

Teacher, I love my job.

The limitations of flying solo

When you start making games, however, you soon start realizing that you have many limitations. Video games are a multidisciplinary medium that require mastering or, at the very least knowledge on: programming and technical skills; graphic design, drawing skills, 3D modelling, animation, rigging; music composing and interpretation, voice acting; writing skills, gameplay design, psychology, anthropology and sometimes history; and if you plan to make a living on it, business management, marketing, leadership and networking or PR skills also come very handy. At the very least, you need player to test your game before release.

You just cannot have knowledge on all those areas, and even if you did, you’d do better specializing. As I once heard, if the same surgeon and anesthetist on the world happened to be the same person, you probably would not like her to perform both roles at the same time with you on the operation table.

Yes, there are some indie developers stars out there who are famous for putting a great game together on their own, but in most of the cases, at least in some areas (most usually, music), they had the help of others.

Get empowered by your team

Developing indie games is very much like playing Dungeons & Dragons. You will not get far in the adventure if all the players in your group play as barbarians. You need a wizard to counter the spells of the necromancer; you need a dwarf to deactivate traps, a healer, and an elf with an arc to avoid physical confrontations. If you start a group with just, say, programmers, you will find yourself unable to reach the quality level you desire for your game more sooner than later.

What is better, working in a multidisciplinary group not only compensate your deficiencies. Having people around with other knowledge means having around other points of views. When you focus on a task, you are working on a vision, and at this point you stop being creative. A look on your job from a teammate means a fresh look, free from the blindness associated to concentrating in a task (in game design, this is well known as the designer blindness). Those looks, those ideas, are very valuable. In most cases, you will discover that many of them are actually impossible to get done. But the mere input will produce a spark in your brain that could become an awesome idea of your own making, one that you wouldn’t have come to if not that input. After all, you are the expert in your area. In other words, working in a multidisciplinary team not only make up your deficiencies, but empowers you.

Want to make a good game? Make friends first. Good indie game come from good partnerships.

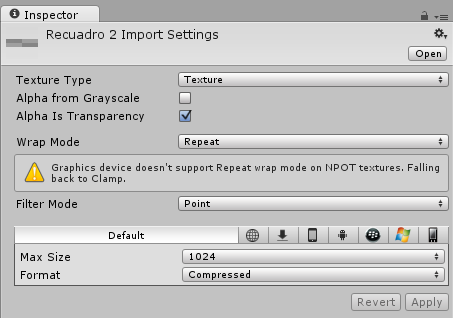

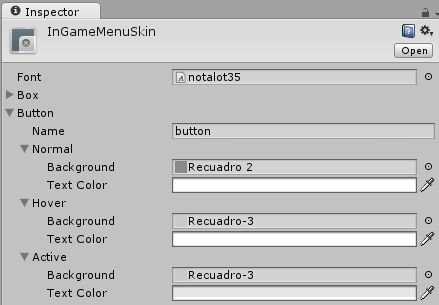

In the script, before declaring the button, you have to declare that you want to use your custom skin:

In the script, before declaring the button, you have to declare that you want to use your custom skin: