This is Part Four of an ongoing series of post describing the design of Turing Adventure. You can try the game here.

Technically, Turing Adventure is possible using chatbot technologies. In contrast to other complex artificial intelligence models, chatbots are based on some very simple principles that were first formulated during the ‘60s, and experienced a resurgence the end of the 90’s – beginning of the century.

They are based on pattern matching: for a certain input, the chatbot is programmed to return some predefined output. This is what is called a rule. Patter matching were the underlying mechanism of the conversational adventures that precedes the graphic adventures, where you had to type some input that matches a pattern to advance in the story. Usually the pattern to match is defined with regular expressions, so through the use of wildcards (i.e.: a symbol that matches any word), a given output could serve as a reply for several inputs. In this way, you do not need then to type exactly what the programmer wanted, nor has the programmer to predefine an endless list of possible input for each option.

Reductionism

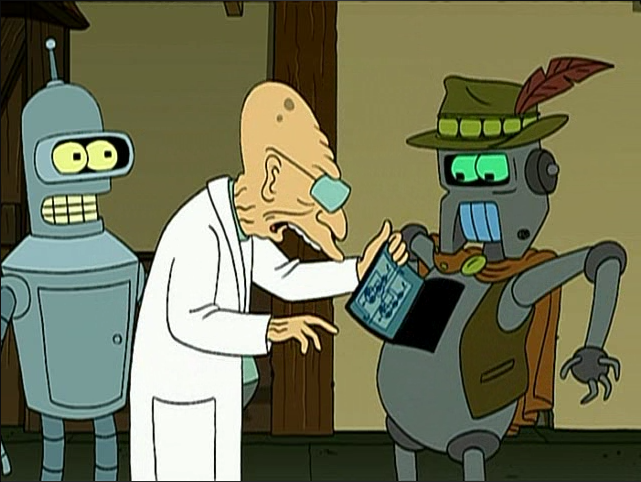

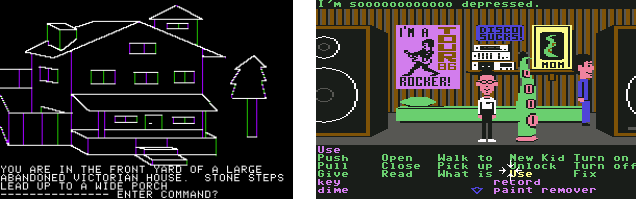

However, with chatbots you can do something that it was impossible with conversational adventures: chat naturally. With the latter, you had limited vocabulary and grammar options, which led conversations to be similar to typing commands. This later evolved nicely to a command based graphic interface (starting the graphic adventure genre), like Lucas Arts games using scumm.

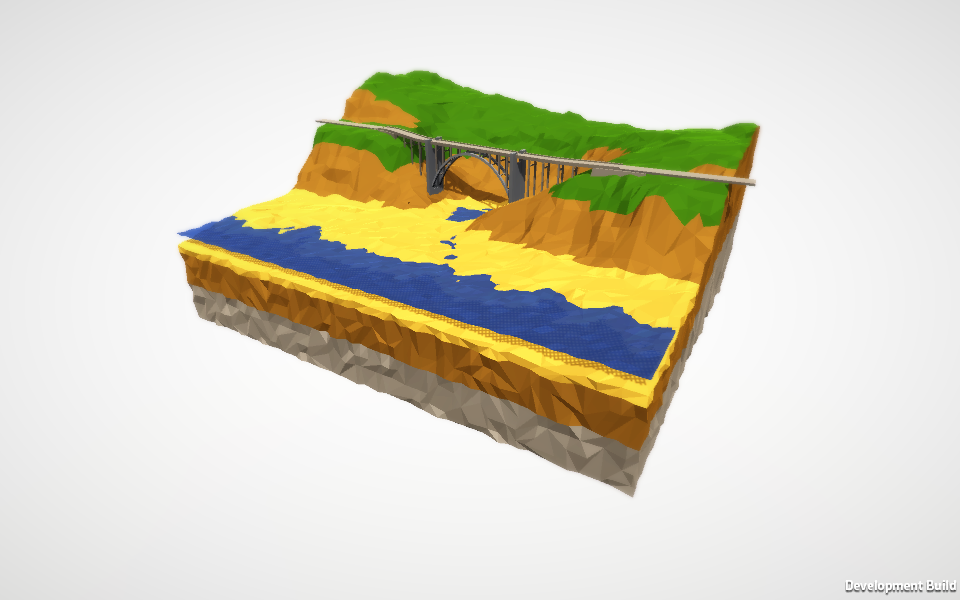

Command based conversational interfaces (left: Mistery House) eventualy evolved to command based graphic interfaces (right: Maniac Mansión)

The natural chat capabilities of chatbots are achieved with a technique called reductionism. This technique consist in matching the user input, but instead of returning an answer to the user, feed it again to the system, modified. This new input should have an equivalent semantic, but it can contains less social etiquette, some orthographic corrections, or more simple grammar. In other words, the transformed input should mean the same, but be shorter, or, reduced. We are transforming a potentially complex input in a simpler-to-match one. This process is repeated until we reach the simplest sentence possible but with the same meaning of the original input given by the user.

If we have a corpus of rules that manage reductionism in the abstract, reducing inputs before treating them, we need to write answers only for those simpler ones. If the user inputs a line that is complex, or that the developer didn’t think about, it would be simplified to a line for which the developer has written an answer.

With a large enough and properly defined corpus of reduction rules, chatbots can provide answers to questions that the programmer of the chatbot had never considered.

It is impossible for the developer think in advance of anything that the user can write. It is then through reductionism how the user is able to speak naturally with the chatbot with good results.

An example

Let’s say that we are adding knowledge to our chat about what is Star Wars. When we ask it What is Star Wars?, the robot may reply: Star wars is a classical Hero’s Journey movie that stands out because of the robots that appear on it.

We can write a rule that represent this dialog line. But what about others ways of asking about Star Wars? For example, if the user says: Excuse me, can you please tell me what do you know about Star Wars? We shouldn’t need to take care of that, nor of any other way to ask about Star Wars. Reductionism should simplify the user input to what is star wars?

What follows is a series of reductions that could simplify the user input in this example (* will work here as a wildcard, matching one or more words):

Original user input: Excuse me, can you please tell me what do you know about Star Wars?

Matched pattern: Excuse me *

Starting a sentence, excuse me only has a phatic and/or courtesy function. We can discard it and feedback the rest of the sentence.

Feedback input: can you please tell me what do you know about Star Wars?

Matched pattern: Can you please *

Again, please is a particle that add no relevant semantic to this sentence. We can chop it and feedback.

Feedback input: can you tell me what do you know about Star Wars?

Matched pattern: can you tell me *

In a sentence with this structure, can you don’t really add any semantic: all of the relevant semantic is carried by tell me. So again, it can be chopped.

Feedback input: tell me what do you know about Star Wars?

Matched pattern: tell me what *

Tell me can really carry some semantic, but in this case, we can discard that, because of the what that follows, which indicates that a question is starting there. We can discard, then tell me. Again, we would not discard tell me in other inputs where it is not followed by an interrogative pronoun and some more words afterwards.

Feedback input: what do you know about Star Wars?

Matched pattern: what do you know about *

All the words in this pattern has meaning, so we cannot really discard some to simplify the question. However, there is a simpler way, with fewer words, to make the same question. So we change the sentence altogether and feed it back to the system:

Feedback input: What is Star Wars?

At this point, the rule we wrote before would match, and the chatbot would reply to the user with the programmed answer.

This can seem rather complicated, but again, we have to consider that the reduction rules has been written beforehand. We only added one rule, and the corpus of reduction rules has sequentially simplify the input to the most basic one we considered. It would work the same way about questing about other topics. It would even work with bits of information that the user teach the chatbots (some of them are able to learn new knowledge from the user – e.g.: Mitsuku).

You can try asking Alice several questions about star wars or other topics here: http://alice.pandorabots.com/

You can also try with Mitsuku. Try to teach her something, and then ask her about it in different ways: http://www.mitsuku.com/

Other techniques

Chatbots can manage default information like its name, its hobbies and so on, and use them in the conversation. That is very helpful to show off the bot personality. But they can also keep track on the context of the conversation. They can remember information that the user provides, like her name, gender and other, and they can use it in later in the conversation. This gives the user a strong feeling of being understood.

They can also answer differently to a given input depending on the topic of the conversation. If, for example, we ask the chatbot, Do you like it?, the chatbot can decide whether it may refers to, for example, ice cream, flowers, or anything else, based on previous interactions, and give a personalized answer for the first two, and a generic answer for the rest of topics.

They can also provide different answers to the same input depending on a previous answer provided by the chatbot. A nice example of that is how to react to a yes/no user input after the chatbot has make her a question.

AIML and Alice

The majority of those techniques, reductionism, context awareness and others, were proposed by doctor Richard S. Wallace from 1995 to the earlier 2000’s, when he proposed the AIML (Artificial Intelligence Mark-up Language) specification. AIML is a XML dialect aimed to the definition of chatbots (although the recursion of the reductionism can allow some backtracking programming, and can be used as a deductive engine like with Prolog). The creation of AIML and dr. Wallace’s work eventually led to the creation of the Alice Foundation, devoted to the promotion and adoption of AIML and open source based chatbots. The Alice Foundation is also responsible for the maintenance of Alice, an open source set of AIML files, with more than 90.000 rules, that conform an open source chatbot (and give its name to the Alice Foundation). Many of those 90.000 rules are designed to manage reductionism in normal English conversation. Thus, to write a new chatbot, Alice conforms a complete set of rules to start from. A new chatbot can be written starting from Alice: discarding many rules that give Alice its personality; adapting or rewriting others (like greets or conversation openings), to reflect the new chatbot personality, and then; writing new rules –that will be triggered by the user directly or through reductionism- that would make the new chatbot different to others.

When writing a chatbot

There are many technical considerations to make when writing an AIML file. Reductionism must be implemented properly to avoid infinite loops. Rules should be well though to make the best use of reductionism; and the new rules should be flexible enough to be modified in the future without many dramas. Many programming patterns and best practices apply here to write AIML rules that comply with those requirements.

However, we cannot forget that when we write a chatbot, we are kind of impersonating a character. That means that before of the technical considerations, we must design the character and write dialog lines, just as we would do when writing a video game or movie plot. The technical work should come after the art work.

In addition, the efficiency of chatbot writing is highly unpredictable; as much as humans beings are. We are dealing with people here, and not people dealing with a given computer interface, but people talking, and of any topic they choose to. Experience is a plus, but it will be impossible to anticipate all reactions, topics and way to express themselves that users will input in the chatbot. That is why testing is paramount. After you write your chatbot, you have to carefully read all the conversations that people have with it. Take notes whenever the chatbot says something that it character counterpart would not say, and fix it. You will never achieve a successful chat with 100% of the conversations, but you can aim for a 95% success rate to declare your chatbot capable and well written.